Names and other personal information are encrypted, however, so they are not at risk.

The flaws, which include insufficient encryption for data sent back and forth via the app, aren’t exclusive to Tinder, the researchers say. They spotlight a problem shared by many apps.

Tinder released a statement saying that it takes the privacy of its users seriously, and noting that profile images on the platform can be widely viewed by legitimate users.

But privacy advocates and security professionals say that’s little comfort to those who want to keep the mere fact that they’re using the app private.

Privacy Problem

Tinder, which operates in 196 countries, claims to have matched more than 20 billion people since its 2012 launch. The platform does that by sending users pictures and mini profiles of people they might like to meet.

If two users each swipe to the right across the other’s photo, a match is made and they can start messaging each other through the app.

According to Checkmarx, Tinder’s vulnerabilities are both related to ineffective use of encryption. To start, the apps don’t use the secure HTTPS protocol to encrypt profile pictures. As a result, an attacker could intercept traffic between the user’s mobile device and the company’s servers and see not only the user’s profile picture but also all the pictures he or she reviews, as well.

All text, including the names of the individuals in the photos, is encrypted.

The attacker also could feasibly replace an image with a different photo, a rogue advertisement, or even a link to a website that contains malware or a call to action designed to steal personal information, Checkmarx says.

In its statement, Tinder noted that its desktop and mobile web platforms do encrypt profile images and that the company is now working toward encrypting the images on its apps, too.

But these days that’s just not good enough, says Justin Brookman, director of consumer privacy and technology policy for Consumers Union, the policy and mobilization division of Consumer Reports.

“Apps really should be encrypting all traffic by default—especially for something as sensitive as online dating,” he says.

The problem is compounded, Brookman adds, by the fact that it’s very difficult for the average person to determine whether a mobile app uses encryption. With a website, you can simply look for the HTTPS at the start of the internet address instead of HTTP. For mobile apps, though, there’s no telltale sign.

“So it’s more difficult to know if your communications—especially on shared networks—are protected,” he says.

The second security issue for Tinder stems from the fact that different data is sent from the company’s servers in response to left and right swipes. The data is encrypted, but the researchers could tell the difference between the two responses by the length of the encrypted text. That means an attacker can figure out how the user responded to an image based solely on the size of the company’s response.

By exploiting the two flaws, an attacker could therefore see the images the user is looking at and the direction of the swipe that followed.

“You’re using an app you think is private, but you actually have someone standing over your shoulder looking at everything,” says Amit Ashbel, Checkmarx’s cybersecurity evangelist and director of product marketing.

For the attack to work, though, the hacker and victim must both be on the same WiFi network. That means it would require the public, unsecured network of, say, a coffee shop or a WiFi hot spot set up by the attacker to lure people in with free service.

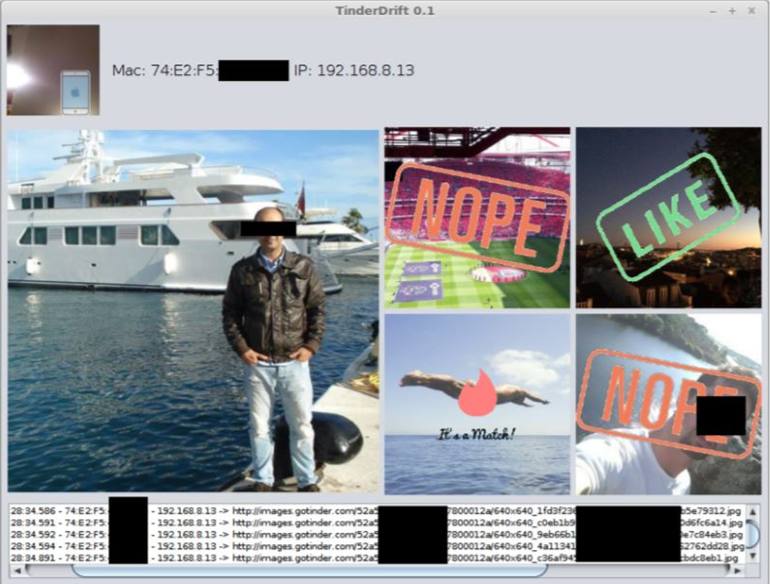

To show how easily the two Tinder flaws can be exploited, Checkmarx researchers created an app that merges the captured data (shown below), illustrating how quickly a hacker could view the information. To view a video demonstration, go to this web page.

Checkmarx researchers made an app to show how they could intercept pictures and swipe information from Tinder users.

PHOTO: CHECKMARX

Why the Security Flaws Are a Problem

The vulnerabilities aren’t likely to result in such harms as identity theft, Dan Cornell, chief technology officer for the cybersecurity firm Denim Group, says, but the invasion of a Tinder user’s privacy could have dire consequences.

“On the surface, you can laugh and say: ‘Ha, ha, ha, it’s public information,’” says Cornell, who has helped design security for other dating apps. “But you’re not really looking at it from a security standpoint.”

Cornell notes that some of the 196 countries where Tinder operates have repressive viewpoints on dating, women’s rights, relationships outside of marriage, and homosexuality. That could put users in danger.

In addition, Checkmarx’s Ashbel proposes a scenario where someone might use the stolen information to demand a ransom, perhaps from a celebrity who doesn’t want his or her activities on Tinder revealed.

And from a technical standpoint, issues with app security reach well beyond Tinder, according to security experts.

While HTTPS has become standard practice for websites, it’s significantly less common for apps, they say. When Tinder launched in 2012, developers could argue that HTTPS encryption slowed the app down too much, but that’s no longer the case.

“In this day and age, there’s absolutely no reason not to move all communications to HTTPS,” says Erez Yalon, Checkmarx’s manager of application security. “There’s no good excuse.”

Casey Oppenheim, co-founder and CEO of the data privacy and security company Disconnect, which has partnered with Consumer Reports to help create a digital privacy standard, notes that Tinder appears to use SSL encryption for most of its connections. The company’s failure to secure the profile images is a “big, but somewhat common, oversight,” he says.

He adds that Apple typically requires apps in its store to use HTTPS but does allow developers to make exceptions. That may explain what happened in this case, he says.

How to Stay Safe

It’s impossible to know for sure without a firm understanding of how the Tinder apps work, but security experts tell Consumer Reports that, in theory, moving to HTTPS would not be that difficult.

And the issue with the swipes could easily be addressed by “padding” the responses with extra data to make the differences in length less obvious.

But Tinder needs to perform both tasks promptly, they say. According to Cornell, hackers are probably looking for ways to take advantage of the vulnerabilities right now, not just on Tinder, but also on other apps with similar setups.

In the meantime, these research findings should serve as a warning to consumers to stay off public WiFi if they want to keep their activities private, says Brookman of Consumers Union.

“If you’re worried that someone might snoop on what you’re doing,” he says, “it’s probably safer to switch to the cellular network.”

Via Consumer Reports.